Help our mission to provide free history education to the world! Please donate and contribute to covering our server costs in 2024. With your support, millions of people learn about history entirely for free every month.

$ 12440 / $ 18000

Persia (roughly modern-day Iran) is among the oldest inhabited regions in the world. Archaeological sites in the country have established human habitation dating back 100,000 years to the Paleolithic Age with semi-permanent settlements (most likely for hunting parties) established before 10,000 BCE.

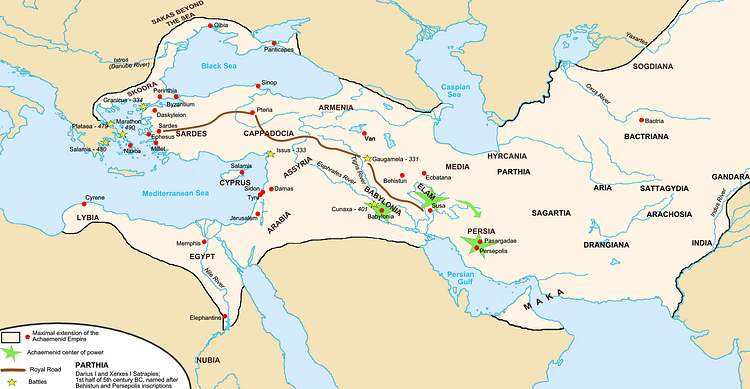

The ancient kingdom of Elam in this area was among the most advanced of its time (its oldest settlement, the archaeological site of Chogha Bonut, dates to c. 7200 BCE) before parts of it were conquered by the Sumerians, later completely by the Assyrians, and then by the Medes. The Median Empire (678-550 BCE) was followed by one of the greatest political and social entities of the ancient world, the Persian Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) which was conquered by Alexander the Great and later replaced by the Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE), Parthia (247 BCE-224 CE), and the Sassanian Empire (224 - 651 CE) in succession. The Sassanian Empire was the last of the Persian governments to hold the region before the Muslim Arab conquest of the 7th century CE.

AdvertisementArchaeological finds, such as Neanderthal seasonal settlements and tools, trace human development in the region from the Paleolithic through the Neolithic and Chalcolithic Ages. The city of Susa (modern-day Shushan), which would later become part of Elam and then Persia, was founded in 4395 BCE, making it among the oldest in the world. Although Susa is often equated with Elam, they were different polities; Susa was founded before even the Proto-Elamite Period (c. 3200-2700 BCE) though it was contemporaneous with Elamite culture.

Aryan tribes are thought to have migrated to the region at some point prior to the 3rd millennium BCE and the country would later be referenced as Ariana and Iran – the land of the Aryans. 'Aryan' should be understood according to the ancient Iranian language of Avestan meaning “noble”, “civilized” or “free man” and designating a class of people, having nothing to do with race - or Caucasians in any way - but referring to Indo-Iranians who applied the term to themselves in the religious works known as the Avesta. The term 'Aryan' interpreted as referencing racial Caucasians was not advanced until the 19th century. Scholar Kaveh Farrokh cites the archaeologist J. P. Mallory in noting:

AdvertisementAs an ethnic designation, the word [Aryan] is most properly limited to the Indo-Iranians, and most justly to the latter where it still gives its name to the country Iran. (Shadows, 17)

These Aryan tribes were made up of diverse people who would become known as Alans, Bactrians, Medes, Parthians, and Persians, among others. They brought with them a polytheistic religion closely associated with the Vedic thought of the Indo-Aryans – the people who would settle in northern India – characterized by dualism and the veneration of fire as an embodiment of the divine. This early Iranian religion held the god Ahura Mazda as the supreme being with other deities such as Mithra (sun god/god of covenants), Hvar Khsata (sun god), and Anahita (goddess of fertility, health, water, and wisdom), among others, making up the rest of the pantheon.

The Persians settled primarily across the Iranian plateau & were established by the 1st millennium BCE.

At some point between 1500-1000 BCE, the Persian visionary Zoroaster (also known as Zarathustra) claimed divine revelation from Ahura Mazda, recognizing the purpose of human life as choosing sides in an eternal struggle between the supreme deity of justice and order and his adversary Angra Mainyu, god of discord and strife. Human beings were defined by whose side they chose to act on. Zoroaster's teachings formed the foundation of the religion of Zoroastrianism which would later be adopted by the Persian empires and inform their culture.

AdvertisementThe Persians settled primarily across the Iranian plateau and were established by the 1st millennium BCE. The Medes united under a single chief named Dayukku (known by the Greeks as Deioces, r. 727-675 BCE) and founded their state in Ecbatana. Dayukku's grandson, Cyaxares (r. 625-585 BCE), would extend Median territory into modern-day Azerbaijan. In the late 8th century BCE, under their king Achaemenes, the Persians consolidated their control of the central-western region of the Bakhityari Mountains with their capital at Anshan.

The Elamites, as noted, were already established in this area at the time and, most likely, were the indigenous people. The Persians under their king Teispes (son of Achaemenes, r. 675-640 BCE) settled to the east of Elam in the territory known as Persis (also Parsa, modern Fars) which would give the tribe the name they are known by. They later extended their control of the region into Elamite territory, intermarried with Elamites, and absorbed the culture. Sometime prior to 640 BCE, Teispes divided his kingdom between his sons Cyrus I (r. 625-600 BCE) and Ararnamnes. Cyrus ruled the northern kingdom from Anshan and Arianamnes ruled in the south. Under the rule of Cambyses I (r. 580-559 BCE) these two kingdoms were united under rule from Anshan.

The Medes were the dominant power in the region and the kingdom of the Persians a small vassal state. This situation would reverse after the fall of the Assyrian Empire in 612 BCE, hastened by the campaigns of the Medes and Babylonians who led a coalition of others against the weakening Assyrian state. The Medes at first maintained control until they were overthrown by the son of Cambyses I of Persia and grandson of Astyages of Media (r. 585-550 BCE), Cyrus II (also known as Cyrus the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) who founded the Achaemenid Empire.

AdvertisementCyrus II overthrew Astyages of Media c. 550 BCE and began a systematic campaign to bring other principalities under his control. He conquered the wealthy kingdom of Lydia in 546 BCE (following the Battle of Thymbra of 547 BCE), Elam (Susiana) in 540 BCE, and Babylon in 539 BCE. By the end of his reign, Cyrus II had established an empire which stretched from the modern-day region of Syria down through Turkey and across to the borders of India. This was the Achaemenid Empire, named for Cyrus II's ancestor Achaemenes.

Cyrus II is unique among ancient conquerors for his humanitarian vision and policies as well as encouraging technological innovations. Much of the land he conquered suffered from a lack of adequate water supply and so he had his engineers revive an older means of tapping underground aquafers known as a qanat, a sloping channel dug into the earth with vertical shafts at intervals down to the channel which would bring the water up to ground level.

Although Cyrus II is often credited with inventing the qanat system, it is attested to earlier by Sargon II of Assyria (r. 722-705 BCE) in the inscription describing his 714 BCE Urartu campaign. Sargon II notes qanats in use around the city of Ulhu in Western Iran which created fertile fields far from any river. Cyrus II, it seems, developed the qanat across a much greater area but it was an earlier Persian invention as was the yakhchal – great domed coolers which created and preserved ice, the first refrigerators – whose use he also encouraged.

Advertisement

Cyrus II's humanitarian efforts are well-known through the Cyrus Cylinder, a record of his policies and proclamation of his vision that everyone under his reign should be free to live as they wished as long as they did so in peaceful accord with others. After he conquered Babylon, he allowed the Jews – who had been taken from their homeland by King Nebuchadnezzar (r. 605-562 BCE) in the so-called Babylonian Captivity – to return to Judah and even provided them with funds to rebuild their temple. The Lydians continued to worship their goddess Cybele, and other ethnicities their own deities as well. All Cyrus II asked was that citizens of his empire live peacefully with each other, serve in his armies, and pay their taxes.

In order to maintain a stable environment, he instituted a governmental hierarchy with himself at the top surrounded by advisors who relayed his decrees to secretaries who then passed these on to regional governors (satraps) in each province (satrapy). These governors only had authority over bureaucratic-administrative matters while a military commander in the same region oversaw military/police matters. By dividing the responsibilities of government in each satrapy, Cyrus II lessened the chance of any official amassing enough money and power to attempt a coup.

The decrees of Cyrus II – and any other news – traveled along a network of roads linking major cities. The most famous of these would become the Royal Road (later established by Darius I) running from Susa to Sardis. Messengers would leave one city and find a watchtower and rest-station within two days where he would be given food, drink, a bed, and be provided with a new horse to travel on to the next. The Persian postal system was considered by Herodotus a marvel of his day and became the model for later similar systems.

Cyrus founded a new city as capital, Pasargadae, but moved between three other cities which also served as administrative hubs: Babylon, Ecbatana, and Susa. The Royal Road connected these cities as well as others so that the king was constantly informed of the affairs of state. Cyrus was fond of gardening and made use of the qanat system to create elaborate gardens known as pairi-daeza (which gives English its word, and concept of, paradise). He is said to have spent as much time as possible in his gardens daily while also managing, and expanding on, his empire.

Cyrus died in 530 BCE, possibly in battle, and was succeeded by his son Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE) who extended Persian rule into Egypt. Scholars continue to debate the identity of his successor as it could either be his brother Bardiya or a Median usurper named Gaumata who took control of the empire in 522 BCE. Cambyses II is said to have assassinated his brother and Gaumata to have assumed Bardiya's identity while Cambyses II was campaigning in Egypt. Either way, a distant cousin of the brothers assassinated this ruler in 522 BCE and took the regnal name of Darius I (also known as Darius the Great, r. 522-486 BCE). Darius the Great would extend the empire even further and initiate some of its most famous building projects, such as the great city of Persepolis which became one of the empire's capitals.

Darius launched an invasion of Greece which was halted at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE.Even though Darius I continued Cyrus II's policy of tolerance and humanitarian legislation, unrest broke out during his reign. This was not uncommon as it was standard for provinces to rebel after the death of a monarch going back to the Akkadian Empire of Sargon the Great in Mesopotamia (r. 2334-2279 BCE). The Ionian Greek colonies of Asia Minor were among these and, since their efforts were backed by Athens, Darius launched an invasion of Greece which was halted at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE.

Love History?Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

After Darius I's death, he was succeeded by his son Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE) who is said to have raised the largest army in history up to that point for his unsuccessful invasion of Greece in 480 BCE. Afterwards, Xerxes I occupied himself with building projects – notably adding to Persepolis – and his successors did the same. The Achaemenid Empire remained stable under later rulers until it was conquered by Alexander the Great during the reign of Darius III (336-330 BCE). Darius III was assassinated by his confidante and bodyguard Bessus who then proclaimed himself Artaxerxes V (r. 330-329 BCE) but was shortly after executed by Alexander who styled himself Darius' successor and is often referred to as the last monarch of the Achaemenid Empire.

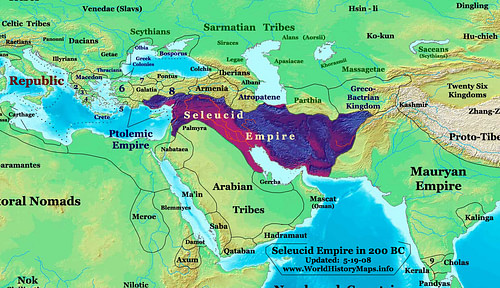

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, his empire was divided among his generals. One of these, Seleucus I Nicator (r. 305-281 BCE), took Central Asia and Mesopotamia, expanding the territories, founding the Seleucid Empire, and Hellenizing the region. Seleucus I kept the Persian model of government and religious toleration but filled top administrative positions with Greeks. Even though Greeks and Persians intermarried, the Seleucid Empire favored Greeks and Greek became the language of the court. Seleucus I began his reign putting down rebellions in some areas and conquering others but always maintaining the Persian governmental policies which had worked so well in the past.

Even though this same practice was followed by his immediate successors, regions rose in revolt and some, like Parthia and Bactria, broke away. In 247 BCE, Arsaces I of Parthia (r. 247-217 BCE) established an independent kingdom which would become the Parthian Empire. The Seleucid king Antiochus III (the Great, r. 223-187 BCE) would retake Parthia briefly in c. 209 BCE, but Parthia was on the rise and shook off Seleucid rule afterwards.

Antiochus III, the last effective Seleucid king, reconquered and expanded the Seleucid Empire but was defeated by Rome at the Battle of Magnesia in 190 BCE and the Treaty of Apamea (188 BCE) resulted in significant losses, shrinking the empire down to less than half its former size. Shortly after this, the Parthian king Phraates (r. 176-171 BCE) seized on the Seleucid defeat and expanded Parthian control into former Seleucid regions. His successor, Mithridates I (r. 171-132 BCE), would consolidate these regions and expand the Parthian Empire further.

Parthia continued to grow as the Seleucid Empire shrank. The Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (r. 175-164 BCE) focused entirely on his own self-interests and his successors would continue this pattern. The Seleucids were finally reduced to a small buffer kingdom in Syria after their defeat by the Roman general Pompey the Great (l. c. 106-48 BCE) while, by that time (63 BCE), the Parthian Empire was at its height following the reign of Mithridates II (124-88 BCE) who had expanded the empire even further.

The Parthians reduced the threat of rebellion in the provinces by shrinking the size of satrapies (now called eparchies) and allowing kings of conquered regions to retain their positions with all rights and privileges. These client kings paid tribute to the empire, enriching the Parthian treasury, while maintaining peace simply because it was in their own best interests. The resultant stability allowed Parthian art and architecture – which was a seamless blend of Persian and Hellenistic cultural aspects – to flourish while prosperous trade further enriched the empire.

The Parthian army was the most effective fighting force of the age, primarily due to its cavalry and the perfection of a technique known as the Parthian shot characterized by mounted archers, feigning retreat, who would turn and shoot back at advancing adversaries. This tactic of Parthian warfare came as a complete surprise and was quite effective even after opposing forces became aware of it. The Parthians under Orodes II (r. 57-37 BCE) easily defeated the triumvir Crassus of Rome at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, killing him, and later defeated Mark Antony in 36 BCE, delivering two severe blows to the might and morale of the Roman army.

Even so, Rome's power was on the rise as an empire founded by Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) and by 165 CE the Parthian Empire had been severely weakened by Roman campaigns. The last Parthian king, Artabanus IV (r. 213-224 CE) was overthrown by his vassal Ardashir I (r. 224- 240 CE), a descendant of Darius III and a member of the royal Persian house. Ardashir I was chiefly concerned with building a stable kingdom founded on the precepts of Zoroastrianism and keeping that kingdom safe from Roman warfare and influence. To this end, he made his son Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE) co-regent in 240 CE. When Ardashir I died a year later, Shapur I became king of kings and initiated a series of military campaigns to enlarge his territory and protect his borders.

Shapur I was a devout Zoroastrian but adhered to a policy of religious tolerance in keeping with the practice of the Achaemenid Empire.

Shapur I was a devout Zoroastrian, like his father, but adhered to a policy of religious tolerance in keeping with the practice of the Achaemenid Empire. Jews, Christians, and members of other religious faiths were free to practice their beliefs, build houses of worship, and participate in government. The religious visionary Mani (l. 216-274 CE), founder of Manichaeism, was a guest at Shapur I's court.

Shapur I was as able an administrator, running his new empire efficiently from the capital at Ctesiphon (earlier the seat of the Parthian Empire), and commissioned numerous building projects. He initiated the architectural innovation of the domed entrance and the minaret while reviving the use of the qanat (which the Parthians had neglected) and the yakhchal as well as wind-towers (also known as wind catchers), originally an Egyptian invention, for ventilating and cooling buildings. He may have also commissioned the impressive Taq Kasra arch, still standing, at Ctesiphon although some scholars credit this to the later monarch Kosrau I.

His Zoroastrian vision cast him and the Sassanians as the forces of light, serving the great god Ahura Mazda, against the forces of darkness and disorder epitomized by Rome. Shapur I's campaigns against Rome were almost universally successful even to the point of capturing the Roman emperor Valerian (r. 253-260 CE) and using him as a personal servant and footstool. He saw himself as a warrior king and lived up to that vision, taking full advantage of Rome's weakness during the Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 CE) to enlarge his empire.

Shapur I lay the foundation for the Sassanian Empire which his successors would build on and the greatest of these was Kosrau I (also known as Anushirvan the Just, r. 531-579 CE). Kosrau I reformed the tax laws so they were more equitable, divided the empire into four sections – each under the defense of its own general for quick response to external or internal threats, secured his borders tightly, and elevated the importance of education. The Academy of Gondishapur, founded by Kosrau I, was the leading university and medical center of its day with scholars from India, China, Greece, and elsewhere forming its faculty.

Kosrau I continued the policies of religious tolerance and inclusion as well as the ancient Persian antipathy towards slavery. Prisoners of war taken by the Roman Empire became slaves; those taken by the Sassanian Empire became paid servants. It was illegal to beat or in any way injure a servant, no matter one's social class, and so the life of a 'slave' under the Sassanian Empire was far superior to slaves' lives anywhere else.

The Sassanian Empire is considered the height of Persian rule & culture in antiquity.The Sassanian Empire is considered the height of Persian rule and culture in antiquity as it built upon the best aspects of the Achaemenid Empire and improved them. The Sassanian Empire, like most if not all others, declined through weak rulers who made poor choices, the corruption of the clergy, and the onslaught of the plague in 627-628 CE.

It was still hardly at full strength when it was conquered by the Muslim Arabs in the 7th century CE. Even so, Persian technological, architectural, and religious innovations would come to inform the culture of the conquerors and their religion. The high civilization of ancient Persia continues today with direct, unbroken ties to its past through the Iranian culture.

Although modern-day Iran corresponds to the heartland of ancient Persia, The Islamic Republic of Iran is a multi-cultural entity. To say one is Iranian is to state one's nationality while to say one is Persian is to define one's ethnicity; these are not the same things. Even so, Iran's multi-cultural heritage comes directly from the paradigm of the great Persian empires of the past, which had many different ethnicities living under the Persian banner, and that past is reflected in the diverse and welcoming character of Iranian society in the present day.